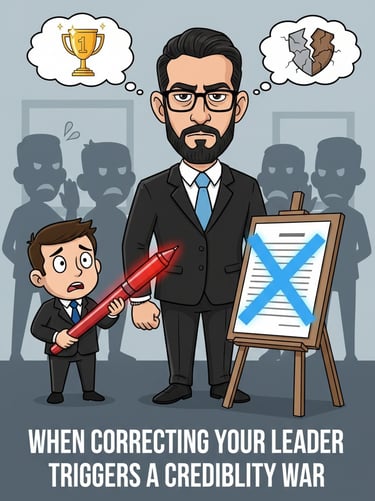

When Correcting Your Leader Triggers a Credibility War

When correcting a leader turns personal, credibility, not performance, but comes under threat. This article explores why leaders sometimes take feedback personally, how ego, power, and psychological safety shape these moments, and what happens when truth triggers defensiveness. The article is grounded in leadership psychology and real-world research, it offers practical guidance on correcting leaders wisely, protecting credibility, and leading with emotional intelligence in high-stakes conversations.

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENTEXECUTIVE COACHING

Mr. Shayan Siddiqui

1/25/20265 min read

How credibility quietly becomes the real issue, and how professionals can navigate it without losing influence or integrity

A leader offers feedback. You listen carefully. You respect the role, the experience, the responsibility. But something is off.

The numbers don’t align.

The assumption is inaccurate.

The conclusion doesn’t reflect what actually happened.

So you respond calmly. Not defensively. Not emotionally. You clarify the point because accuracy matters, and because you care about the outcome.

And then the room changes.

The conversation tightens. The tone cools. The exchange slows in a way that feels deliberate. What should have remained a professional discussion quietly shifts into something else. It is no longer about performance, results, or improvement.

It becomes about authority, image, and who is allowed to be right.

Many professionals struggle to name this moment, but they feel it immediately. It is the moment when feedback turns personal, and credibility becomes contested.

This article is about understanding why that shift happens, what is really at play beneath the surface, and how thoughtful professionals can respond without escalating conflict or diminishing themselves.

Why Correction Often Feels Like a Threat

On paper, correction should be neutral. In healthy systems, it is even welcomed.

In reality, correction often lands very differently, especially when it flows upward.

For many leaders, their role is tightly connected to their sense of competence and legitimacy. Over time, decision-making authority stops feeling like a function of the job and starts feeling like proof of capability. When that sense of capability is questioned, even subtly, the reaction is rarely logical.

Psychological research has long shown that when people perceive a threat to their competence or authority, their ability to remain open narrows. The brain prioritizes self-protection over reflection. Defensiveness replaces curiosity. Control replaces dialogue.

This is not about bad intentions. It is about unmanaged human instinct.

To the person offering correction, the goal is clarity.

To the person receiving it, the experience can feel like exposure.

The Role of Status and Identity

Leadership is not just a position, it becomes part of identity.

When someone corrects a leader, especially in real time. it can register as more than disagreement. It can feel like a public questioning of judgment, expertise, or legitimacy. Even leaders who value collaboration may struggle in these moments, not because they reject learning, but because their status feels unsettled.

In those moments, the response is rarely conscious. The leader may become more rigid, more formal, or subtly dismissive. They may reassert authority, shift the focus, or revisit the issue later in ways that feel punitive or political.

From the outside, this behavior can look petty or insecure. From the inside, it often feels like regaining balance.

Understanding this dynamic does not excuse it, but it does explain why these moments escalate faster than logic alone would suggest.

When the Environment Makes Things Worse

Whether correction becomes constructive or combative depends heavily on the environment in which it occurs.

In workplaces where speaking up has historically carried risk, people learn to measure every word. Accuracy becomes secondary to survival. Silence becomes a strategy. Over time, these environments reward compliance more than clarity.

In contrast, environments that consistently reinforce respectful challenge tend to normalize correction. Leaders in these settings are not immune to discomfort, but they are less likely to experience correction as a threat to their standing.

When credibility battles occur repeatedly, they are rarely isolated incidents. They are signals of systems that have not clearly separated authority from infallibility.

How Credibility Conflicts Actually Escalate

These situations almost never explode immediately.

They unfold quietly.

A factual correction is offered.

A leader feels exposed.

The interaction becomes emotionally charged beneath the surface.

Future conversations carry tension.

Trust erodes in small, unspoken ways.

Eventually, people stop discussing ideas and start managing impressions. Meetings become careful instead of honest. Decisions are framed to avoid friction rather than to serve outcomes.

What began as a moment of correction becomes a slow credibility standoff.

Power Has Side Effects—Even for Good Leaders

One of the less comfortable truths about leadership is this: authority can distort self-perception.

The more responsibility someone holds, the less often their assumptions are challenged. Over time, this creates a subtle overconfidence, not arrogance, but certainty. Leaders begin to trust their instincts more and question opposing views less.

This is not a flaw of character. It is a byproduct of power.

Without intentional effort, leaders can become less receptive to correction precisely when their decisions matter most. When that happens, the people around them must decide whether to protect truth, protect themselves, or attempt to do both.

How to Correct Without Creating a Contest

Correcting a leader successfully is rarely about proving a point. It is about preserving dignity while protecting accuracy.

Professionals who navigate these moments well tend to focus on shared goals rather than personal positions. They anchor discussions in data, context, and outcomes instead of judgments. They invite alignment rather than confrontation.

Language matters. Timing matters. Tone matters. But most of all, intention matters.

When correction is framed as joint problem-solving, it is easier to receive. When it feels like exposure, resistance is almost guaranteed.

Even leaders need safety in order to stay open.

When Skillful Communication Still Isn’t Enough

Sometimes, even the most thoughtful approach fails.

Some environments are not ready for challenge. Some leaders are not equipped to separate disagreement from disloyalty. In those cases, persistence can become self-sabotage.

Strategic professionals learn to read these contexts carefully. They document rather than debate. They ask questions instead of offering conclusions. They build credibility across relationships rather than relying on a single authority figure.

This is not avoidance. It is discernment.

Protecting your integrity does not always require winning the moment. Sometimes it requires staying effective long enough to influence outcomes indirectly.

What Leadership Maturity Really Looks Like

Leadership maturity is revealed in moments of discomfort.

It shows up in the ability to listen without defensiveness, to regulate emotion under challenge, and to treat correction as information rather than insult. Leaders who can do this create environments where truth travels faster than fear.

Professionals who understand this dynamic learn to balance honesty with awareness. They do not silence themselves, but they also do not confuse bluntness with courage.

Because truth delivered without care creates resistance.

And empathy without truth creates stagnation.

Strong leadership and strong followership requires both.

References

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Wiley.

"Supports the discussion on psychological safety, speaking up, and how leaders respond to correction".Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284.

"Directly underpins the explanation of how power alters receptiveness, self-perception, and emotional regulation".Fast, N. J., & Chen, S. (2009). When the boss feels inadequate: Power, incompetence, and aggression. Psychological Science, 20(11), 1406–1413.

"Grounds the article’s argument about ego threat and defensive leadership behavior when competence feels challenged".Detert, J. R., & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 461–488.

"Supports the sections on silence, self-protection, and credibility management in unsafe environments".Schein, E. H., & Schein, P. (2018). Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust. Berrett-Koehler.

"Anchors the discussion on leadership maturity, openness to correction, and relational authority.